Most of the

information on this page was taken from a series of booklets published

by the Grand Lodge of Connecticut.

Excerpted

from Bay View Lodge No.120, Connecticut A.F.&A.M.,

Niantio, CT. Used with permission.

The true origins of Freemasonry are clouded in both history and mystery.

"Modern" Freemasonry dates back to the forming of the first

Grand Lodge in England in 1717, though historical analysis shows Masonry

to be much older. Written records of modern Masonry's precursors date

back to the 14th century, while other aspects of Masonry date back to

thousands of years B.C.

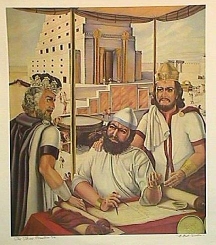

There is much speculation as to the

origins of Freemasonry. The earliest known use of the Square and

Compasses symbol was its carving in an altar from 3800B.C. There is

evidence that an elementary type of craft association existed as early

as the time of King Solomon's Temple (about 1012 B.C.). That structure

was the architectural masterpiece of its day; and because of the

relationship between those early masons and the building of that

spiritual edifice, Masonic tradition is rich in references to its

construction.

There is much speculation as to the

origins of Freemasonry. The earliest known use of the Square and

Compasses symbol was its carving in an altar from 3800B.C. There is

evidence that an elementary type of craft association existed as early

as the time of King Solomon's Temple (about 1012 B.C.). That structure

was the architectural masterpiece of its day; and because of the

relationship between those early masons and the building of that

spiritual edifice, Masonic tradition is rich in references to its

construction.

The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans

taught higher education in schools resembling lodges, and protected

their learning, and at times their existence when their teachings were

proscribed, with secret signs and symbols. Guilds of stonemasons were

operative at this time, building the great architectual works of the

Roman Empire. Cleopatra's Needle also has symbols used by modern Masons

in its base. How these associations and secret societies of the ancient

world led to modern Freemasonry is uncertain.

What is certain is that Freemasonry's

direct predecessors are the guilds of operative stonemasons that built

the great cathedrals of Europe. In England during the 10th century these

guilds became subject to regulation by the Crown. In the Regius Poem

there is definite reference to Athelstane, the King of England, who

presided over a convocation of masons at York and established a series

of regulations to govern the individual groups or lodges. A study of

these regulations reveals a marked similarity to our own ancient

constitutions and illustrates the strictness with which the operative

masons kept the secrets of their trade and cared for each other and each

other's families. Because of their importance in building cathedrals and

other structures, masons enjoyed privileges denied to other trades and

guilds, most notably the freedom to travel from country to country and

from place to place as needed. Because of this, they became known as

Free-masons.

After the 11th century, the guilds of

masons became more settled, though some there was still some traveling

from one country to another throughout Europe. There are definite

references in the archives of various cathedrals and monasteries

indicating that "lodges" of masons were responsible for the

erection of these edifices. The lodge was a temporary building to house

the artisans while they were employed in their daily work.

After the 11th century, the guilds of

masons became more settled, though some there was still some traveling

from one country to another throughout Europe. There are definite

references in the archives of various cathedrals and monasteries

indicating that "lodges" of masons were responsible for the

erection of these edifices. The lodge was a temporary building to house

the artisans while they were employed in their daily work.

By the 14th century, however, many lodges

had become permanent. Surviving records are frequent, allusions in

historical narrative more common, and by the 16th century definite

references to Masonic lodges are not uncommon.

As the centuries went on, cathedral

building declined, and as a result, so did the numbers of operative

masons. To supplement their numbers, they began accepting individuals

outside the profession who were regarded as desirable members, referring

to them as "speculative masons" who were taught religious and

moral lessons using the tools of masonry as symbols, rather than the

craft of the stonemasons. By the 17th century this had become common

practice and the membership of some lodges was made up largely of men

who were neither directly nor indirectly associated with the trade of

masonry. Elias Ashmole, founder of the famous library at Oxford

University, recorded in his diary his initiation into a lodge of masons

in 1646.

As cathedral building waned, lodges were

weakened by lack of purpose and the need for strengthening lodges became

apparent. In 1717 four lodges met in London to form the Grand Lodge of

London, which gradually expanded to become the Grand Lodge of England.

About the same time, a Grand Lodge was formed in Ireland, and shortly

thereafter one in Scotland. The Grand Lodge of London published a book

of constitutions known as "Anderson's Constitutions", the

first truly Masonic book in modern times. Copies still exist. Gradually

all connection with operative masonry was abandoned and Freemasonry

became what it is now, a purely symbolic philosophic and benevolent

institution.

Freemasonry in America

Masonry was first introduced into the colonies by individual masons,

some of whom organized new lodges by "immemorial right." A few

charters were obtained from the Grand Lodges of England, Scotland, and

Ireland. As early as 1733, Provincial grand Masters were appointed to

regulate the craft on this continent. A second Grand Lodge at Boston was

chartered from Scotland. Its first Grand Master, Dr. Joseph Warren, gave

his life for liberty at the Battle of Bunker Hill. In 1751 another Grand

Lodge was formed in London, which also chartered lodges in America. Many

lodges in the British regiments that fought in America were chartered

from Ireland.

By 1775 lodges from these several sources

were in existence all along the Atlantic coast from Nova Scotia to the

West Indies. During and after the Revolutionary War, lodges in the

colonies began to form independent Grand Lodges in their states.

Virginia holds the honor of forming the first independent Grand Lodge,

in a special convention held at Williamsburg in 1778, while the British

forces still threatened the colonial capitol of Jamestown, a few miles

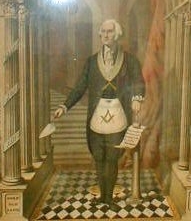

away. George Washington was urged to become the first Grand Master of a

National Grand Lodge of the United Sates, but brother Washington

refused, believing the idea dangerous to local self-government of the

Craft.

By 1775 lodges from these several sources

were in existence all along the Atlantic coast from Nova Scotia to the

West Indies. During and after the Revolutionary War, lodges in the

colonies began to form independent Grand Lodges in their states.

Virginia holds the honor of forming the first independent Grand Lodge,

in a special convention held at Williamsburg in 1778, while the British

forces still threatened the colonial capitol of Jamestown, a few miles

away. George Washington was urged to become the first Grand Master of a

National Grand Lodge of the United Sates, but brother Washington

refused, believing the idea dangerous to local self-government of the

Craft.

Many colonial Masons were involved in the

American Revolution. George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Paul Revere,

John Hancock, John Paul Jones - even Benedict Arnold - were all Masons.

In addition, a free black man named Prince Hall was made a Mason, along

with 14 of his friends, on March 6, 1775. They would eventually form

African Lodge No. 459, which would later develop into a world-wide

organization for black Masons with approximately 250,000 members.

The period of the American Revolution

also saw the first American Indian to be made a Mason. Thayendangea was

the son of the chief of the Mohawks in the 1750's, and was brought up in

the household of a prominent British administration official, Sir

William Johnson, who was also a Freemason. Johnson gave him the name

Joseph Brant, and when Brant was an adult, he fought several battles

against the French with Johnson. Brant became Johnson's personal

secretary, and by the time of Johnson's death in 1774, Brant had become

accepted by the British adminsitration. Brant travelled to England in

1775, and was made a mason in a London lodge in 1776. He then returned

to America to enlist the Mohawks in the fight against the American

rebels. The Mohawks, under the command of Col. John Butler and Brant,

attacked and massacred the Americans in several battles, and captured

prisoners were turned over to the Mohawks to be tortured to death.

Brant, however, took his masonic oaths seriously, and in a few recorded

instances, released prisoners who made masonic signs as they were about

to be tortured. After the war, Brant became a member of St John's Lodge

of Friendship No.2 in Canada, of which Col. Butler had become Master,

before returning to the Mohawks in Ohio.

|